Every good vineyard tour should begin with an exercise in imagination. For Oregon winegrowers operating along the route of an ancient and sizable series of floods, that tour should invite you to picture everything from Milton-Freewater to Eugene swimming in 400 feet of water. Because when the Missoula Floods came charging through the region thousands of years ago, that was quite literally the scene.

“The first of the Missoula Floods was the biggest freshwater flood in the world,” says Scott Burns, a longtime professor of geology at Portland State University. “In fact, it was one of the greatest geological events in the [history of the Pacific] Northwest and the world.”

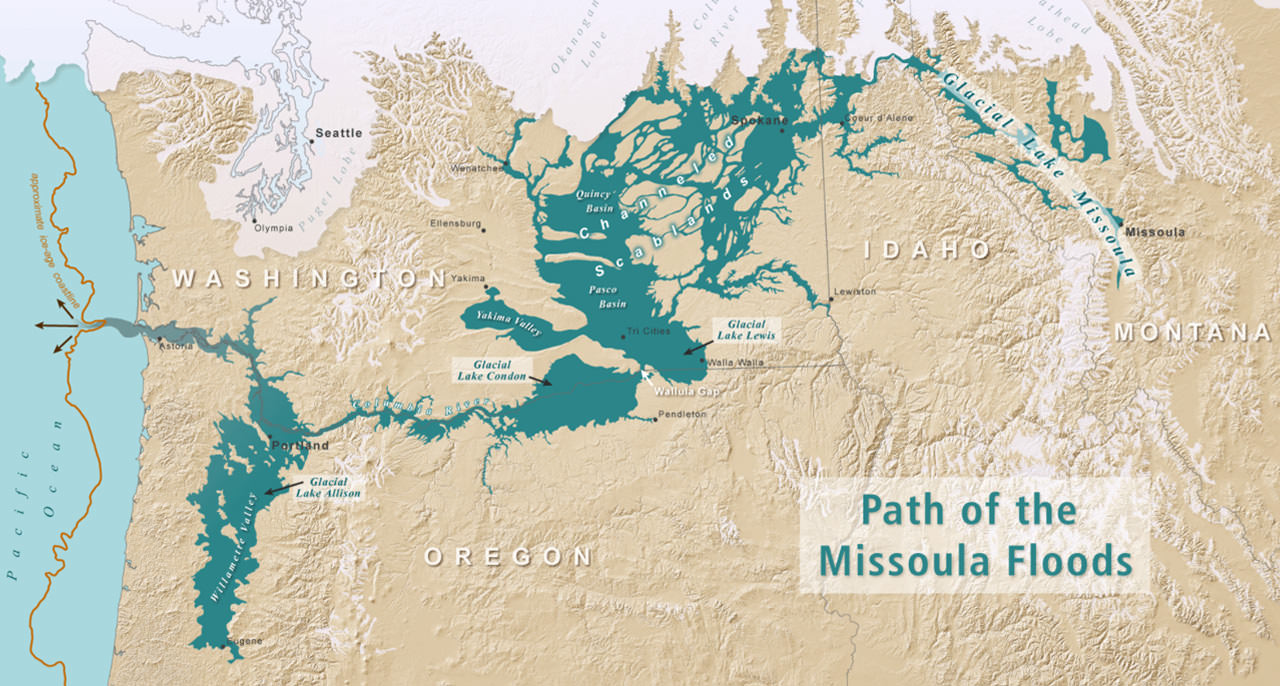

Affecting 16,000 square miles of land, the floods helped create some of the most iconic physical features in the West. Peak flow is estimated at 10 million cubic meters of water per second. That’s enough to separate mountain ranges, carve out scablands and blanket entire regions in new layers of vineyard-friendly earth.

Driving west along the Columbia River, you’re essentially tracing the course of these monumental floods. And you’re doing so at nearly the same pace, as the strongest surges reached barreling speeds of 70 to 80 miles per hour. The dramatic, often rugged mold that unfurls en route makes a lot more sense with the battering Missoula Floods in mind.

With wine, you get to both observe this great chapter in Pacific Northwest geological history and taste its ways. Vineyards function like stoic survey crews, pulling up characteristics from long-ago environmental shifts and presenting them through wildly unique wines.

The best way to take in the Missoula Floods is to trace their dramatic journey through several of Oregon’s distinct grape-growing regions, enjoying the wine culture they helped create.

The Sensory Legacy of the Floods

Not too long ago, geologically speaking, a giant ice dam held the massive Lake Missoula in check in western Montana. At roughly 30 miles wide and 2,000 feet tall, these frozen natural floodgates were among the largest on the planet. When they gave way during a series of floods between about 12,000 and 18,000 years back, the cataclysmic surge of water carved out an entire landscape, from the Rocky Mountains to the Willamette Valley.

The Missoula Floods are to the Pacific Northwest as The Beatles are to music. Intensely impactful, deeply influential and countlessly referenced, the floods redrew topographic maps, tossed bus-size boulders like confetti, and established some of the most prized and diverse soils around. The wine world, with its keen focus on terroir, not only benefits from such shapeshifting — it celebrates and reflects it through expressive wines.

“The Missoula Floods are to the Pacific Northwest as The Beatles are to music. Intensely impactful, deeply influential and countlessly referenced.”

The Truly Unique Rocks District

The Rocks District sits in a small pocket of land just outside the town of Milton-Freewater. Granted official AVA status in 2015, it is considered one of the most unique appellations in the New World.

Although it’s set above the Missoula Floods line, the appellation is part of the larger Walla Walla Valley, where a receding ice shelf sparked the floods long ago. Subsequent forces of nature further molded the area, namely extreme erosion in the nearby Blue Mountains. Massive amounts of soil and cobble — hence, “the Rocks” — cascaded into what is now the appellation via the Walla Walla River.

“It’s probably the most terroir-driven AVA of the 280 or so out there in this country,” says Kevin Pogue, geologist and author of the petition for the appellation.

It’s the only AVA in America defined by a single soil (Freewater) and a single geological feature (alluvial fan). As such, the Rocks is fiercely singular, both physically and in terms of wine. The cobble-strewn soil resides within a neat, 5.9-square-mile area.

At SJR Vineyard, the border is remarkably stark, with softball-size rocks coming to an abrupt stop just past the last rows of vines. The vineyard was founded by Steve Robertson, who worked with Pogue for years defining the appellation. The vineyard’s fruit funnels into his own label, Delmas, as well as other standout producers in the Milton-Freewater area.

“The North Star for us was always distinctiveness,” says Robertson, on his family landing here. “I don’t care where in the world you are, you’re not going to be able to draw the line as straight as you can here.”

The wines from the Rocks, mostly Rhone in variety, tend to show briny, umami characteristics. The area’s minimal rainfall (12 inches a year) and long, warm growing season lead to fullness and personality on the palate. Furthermore, the rocks themselves radiate heat, providing warmth right near the rootstock and fruit clusters. The area is often compared to the famous French region Châteauneuf-du-Pape.

“The best soil for growing grapes is crappy soil,” Burns says. “It’s all about vigor.” He says that when now-lauded wineries like Cayuse Vineyards first arrived in the Rocks, the area was deemed worthless “bottomland.” Several years later, the 2005 Cayuse Armada Syrah became the first wine made from Oregon-grown fruit to score a perfect 100 points in Robert Parker’s “Wine Advocate.” And in 2017 Cayuse founder Christophe Baron was named winemaker of the year by Wine Enthusiast.

With just 14 percent of viable land under vine, there’s tremendous room for growth. “Almost everything about the wines here screams ‘Rocks,’” Pogue says. “And more people will come in and put their stamp on it.”

Tour stops in the Rocks: For a chance at gorgeous syrahs, hop on the waiting list at Delmas. Explore a historic building and sample wines and ciders at Watermill Winery in Milton-Freewater. Pair these expressive wines with equally tasty grub at Milton City Pizza Co.

From A to Z in the Columbia River Gorge

In the Columbia River Gorge, it’s all about diversity. Pronounced variations in elevation and climate yield an eclectic family of resident wine grapes. Within a short drive, you can taste everything from estate pinot noir to cab franc. “You go from Burgundy to Bordeaux in 20 miles here,” Burns tells me.

The AVA was officially established in 2004. Often deemed the world’s capital of windsurfing, the Gorge is synonymous with gusty conditions. This tempers the region, making it a cooler growing area by average temperature than Burgundy — resulting in smaller, tighter grape clusters with more concentrated flavors.

Soils also play a role — an earthy cocktail of lahar, loess, silt, sand and volcanic components. Some vineyards, like Analemma Wines in Mosier, operate on either side of the Missoula Floods line. That means working with younger, marine sedimentary soils down low and ancient volcanic soils above (think Jory, the famous higher-elevation soil in the Willamette Valley and Oregon’s official state soil).

“Visual evidence of the Missoula Floods, persistent winds and steep hillsides set the stage for unusual expressions grown within a compelling context of wild lands,” says Analemma’s Kris Fade. The winery makes syrah, chardonnay, mencia, trousseau, pinot noir and more.

“The Mosier Valley tells the story of the floods like an open textbook,” she adds. “Cobblestones and erratic boulders made of granite lay as proof beside planting sites across the valley.”

Fade says it’s possible to see the “bathtub ring” effect of the floods here, where the high-water mark lapped topsoil away.

Fade compares the Gorge to Galicia in Spain, each with stark topography, a dramatic river canyon and a convergence of climates. “The varieties we have planted in Mosier reveal our strong curiosity in the likeness of these two regions and the possibilities for vibrant, Spanish-inspired wines in the Columbia Gorge,” she says.

“Wines from the Gorge tend to be vibrant and approachable with naturally lower levels of alcohol,” Fade says. “This presents new expressions in American winegrowing.”

Tour spots in the Gorge: In Mosier, chat with Kris Fade about the floods while tasting her wines at Analemma Wines, which even has an interpretive soil display in its tasting room. Also visit nearby Idiot’s Grace and Garnier Vineyards in the charming town of Mosier. In Hood River, sample estate wines made by a Burgundian vintner at Phelps Creek Vineyards, check out the wilder side of Gorge viticulture at Hiyu Wine Farm, and enjoy a meal at Celilo Restaurant and Bar, about 5 miles north in the downtown district.

If You Go:

- Find plenty of options for food, drink and hands-on farm experiences along the East Gorge Food Trail.

- Enjoy Oregon wine country now and later by taking a bottle home with you. Remember that Oregon wines fly free on Alaska Airlines.