A few years ago, Black students at my alma mater, University of Oregon, pushed to rename Deady Hall — named for Matthew Deady, Oregon’s first federal judge and author of Oregon’s Black-exclusion laws, which began in the 1840s. The proposal was met with fierce backlash from some alums and community members who wanted to keep the name for history’s sake, and it was initially rejected. The name change was ultimately approved in 2020, and the building is now known as University Hall.

One can’t help but wonder: What if the university had named the building after a Black person who contributed to the fabric of the university, in spite of the residue of Oregon’s exclusion laws?

In summer 2021, I got to take part in a celebration for the newly renamed Ben Johnson Mountain in Southern Oregon, a 4,500-foot peak in the Siskiyous in the Rogue River National Forest about 14 miles southwest of Medford. According to local archives, Benjamin Johnson was a blacksmith who worked in Uniontown (a town in Jackson County) in the 1860s and made his home on the mountain during Oregon’s gold rush.

The peak is one of just a few place names in Oregon known for a Black person. It was formerly known as “Negro Ben Mountain,” and prior to 1964, it was known as a more derogatory racial slur.

Oregon Black Pioneers worked to support historian Jan Wright’s proposal for the latest name change in 2017. After a lengthy process, the Oregon Geographic Names Board accepted the proposal in late 2020 and renamed it Ben Johnson Mountain.

To commemorate the renaming, Oregon Black Pioneers sponsored a weekend of events in Jacksonville in summer 2021, culminating with a hike up Ben Johnson Mountain and a celebration to honor the history. “So much of our past involved having very close relationships to the land, and I think we’re removed from that in a lot of ways,” says Zachary Stocks, executive director of Oregon Black Pioneers. “A hike is a perfect way to celebrate Ben Johnson’s life on the mountain, where he built a cabin and worked and lived for over two years.”

Reaching the Top

Visitors can access Ben Johnson Mountain via Cantrall Buckley Park, a picnic spot and campground along the Applegate River, about 10 miles southwest of downtown Jacksonville. To reach the trailhead, you’ll need to first drive 5 miles up a single-lane road that allows you to survey surrounding Jacksonville below. (For the uninitiated, this drive may be a journey in itself; a four-wheel drive is recommended.) Upon reaching the parking area and yellow gates, the adventure begins on foot.

Hikers can make their way along a winding 1.1-mile trail that features aerial views of the Rogue Valley peeking through the abundance of trees that line each side of the path. Views of the trail as you round the corners are often as eye-catching as the cityscapes below. Meanwhile, the path up is steep enough to get the heart rate going while still being accessible for novice hikers.

The last 1,000 feet takes a steep, rocky turn. By the time you reach the top — a grassy, tree-covered plateau — it’s impossible not to feel more in touch with Ben Johnson Mountain and its namesake. The trek, as well as the drive to get there, is a small journey when you recognize that Ben Johnson made this trip every day in a state where he was not legally allowed to live. Finding the beauty in his perseverance through this ugly history is what these types of activities simulate, in a small way.

More Renamings on the Horizon

Oregon Black Pioneers is attempting to rename several other Oregon locations with the word “negro” in the place name. This process includes researching who these places may have been named after, and if that information is unavailable, identifying Black figures whose names might also honor the destinations.

“This is ongoing work and it’s statewide work,” says Stocks. “We work all over the state of Oregon, because wherever there have been white people in Oregon, there’ve been Black people in Oregon.” In the meantime, activities like the recent renaming ceremony showcase the potential fruits of such research.

Supporting Local Enterprises

The renaming celebration festivities began with wine-tasting events at Schultz Glory Oaks and Quady North (among many award-winning wineries in Rogue Valley Wine Country), leading into the centerpiece of the evening, a picnic at the Southern Oregon Historical Society’s historic Hanley Farm. The 1857 working farm and museum is open to visitors only during public or private events, but attendees could take self-guided tours of the farm and hop into guided discussions about Southern Oregon’s Black history.

Oregon Black Pioneers, Southern Oregon Historical Society and the Southern Oregon University Laboratory of Anthropology provided a variety of historical materials and artifacts about Ben Johnson and other regional Black history from prior to statehood through the present day.

Picnic guests dined on food by Freddie Lee’s Seafood Smorgasbord, based in Central Point, which highlighted the food cart’s delicious fish, shrimp and chicken offerings, and shined a spotlight on a local Black-owned business.

The celebration demonstrated what’s possible when we support more Black-led efforts that engage with history and build community in fun, interactive ways. “That was really intentional,” says Stocks. “Oregon is one of the whitest states in America. Anytime we can get groups of Black people together, it’s a reason to celebrate, and we have a lot to be thankful for with the Ben Johnson story. We wanted to really go all out with this.”

Learn More:

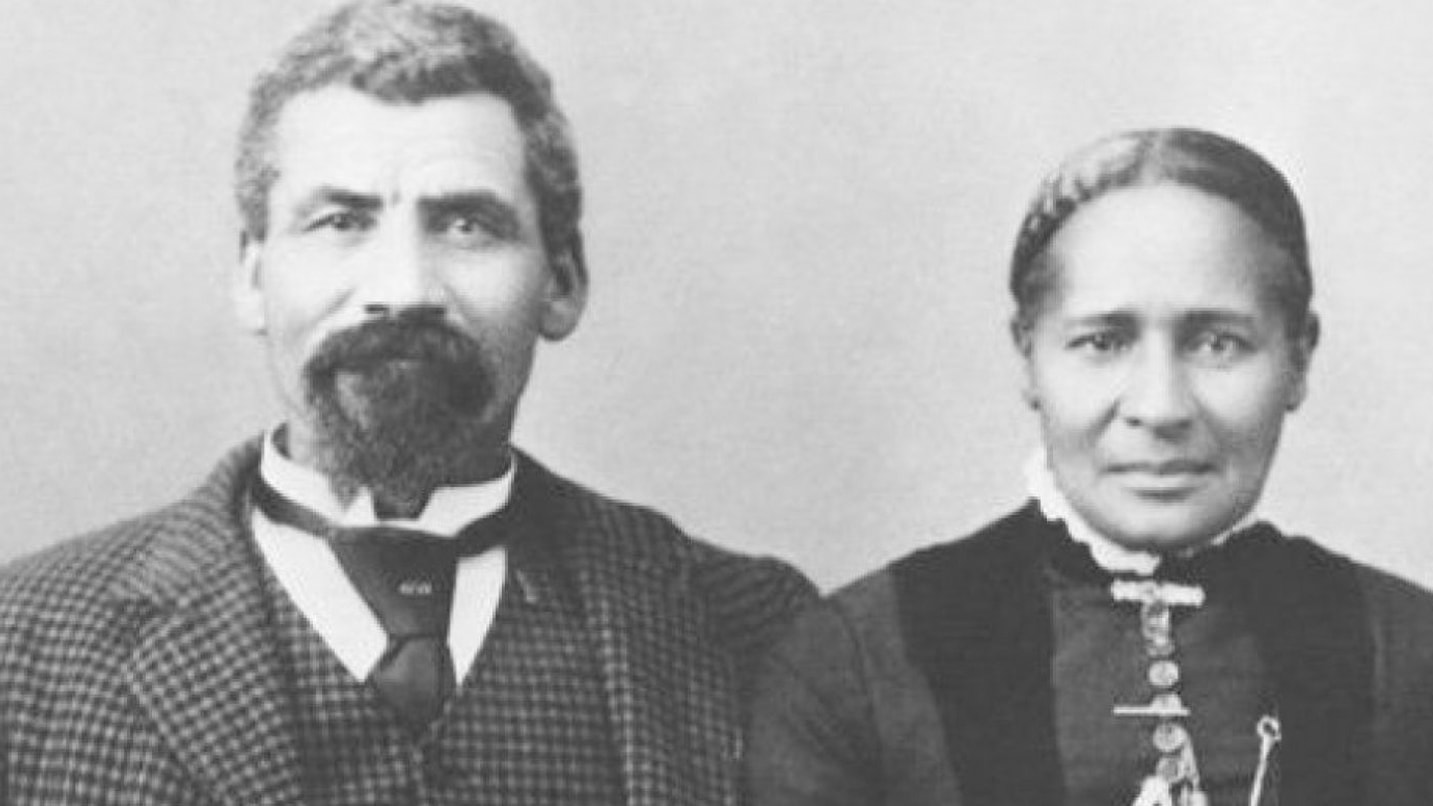

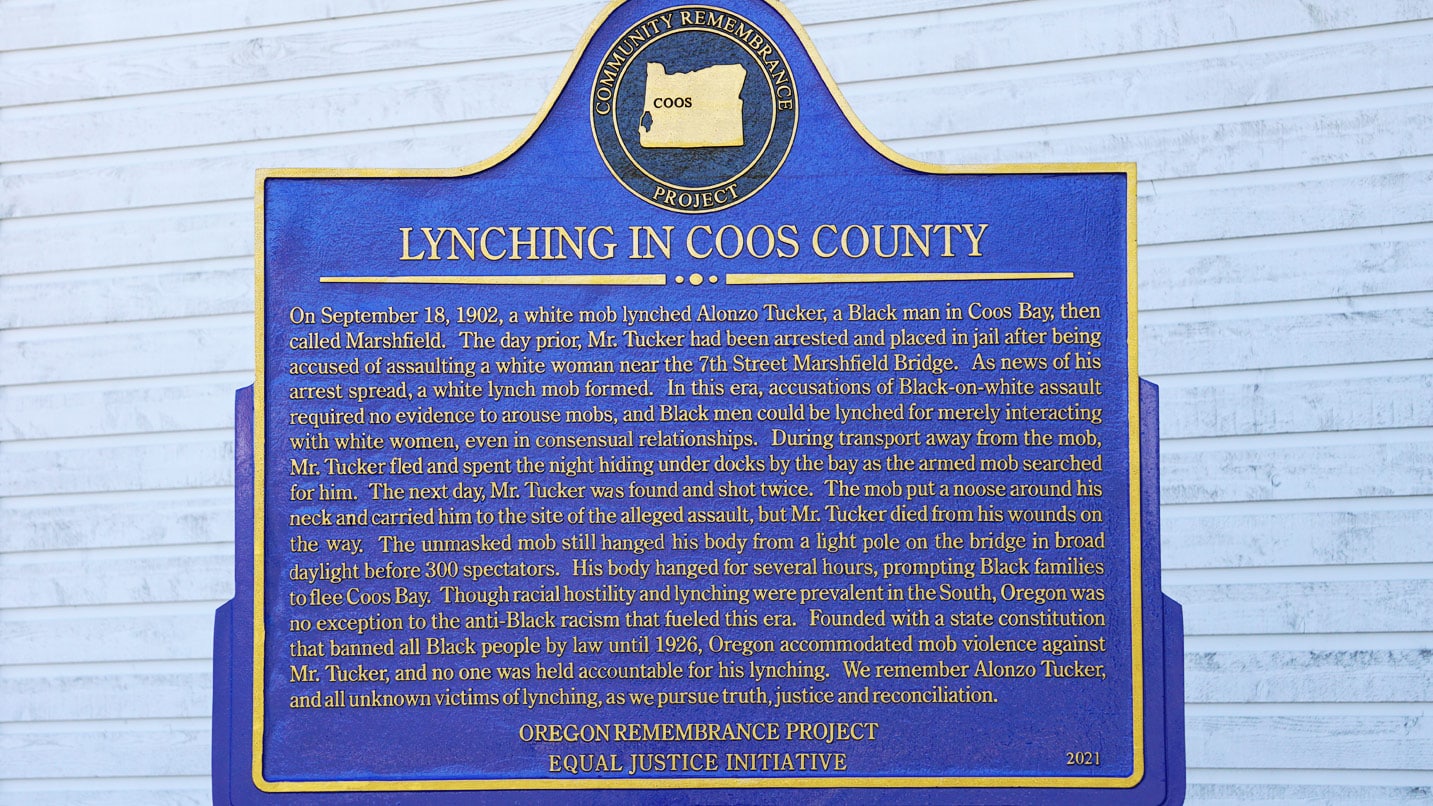

The renaming of Ben Johnson Mountain is one part of Oregon’s acknowledgement and reconciliation efforts. Hundreds gather each year in Coos Bay to recognize Alonzo Tucker, victim of the only documented lynching in Oregon’s history, in 1902. Visitors have collected the soil from where Tucker was lynched to be displayed in a glass jar at the Coos History Museum as well as the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Alabama. Visitors to the Coos History Museum can read about the Oregon Remembrance Project and the history of Alonzo Tucker through the museum display and a new two-sided Equal Justice Initiative historical marker, installed on Juneteenth 2021.

In Waldport, a life-sized bronze statue of Louis Southworth, a Black homesteader, was unveiled in 2022 at the Alsea Bay Bridge Interpretive Center. Southworth came to Oregon in 1853, and made his home in Buena Vista, at the time a bustling community on the Willamette River a little northeast of Corvallis. With his music-playing skills, he earned enough money to buy his freedom. In 1880, his family moved west, staking claim to land a few miles east of Waldport on a creek feeding into the Alsea River. The bronze statue will be placed in the new Louis Southworth Park.