On a clear day, the view from the South Jetty Observation Tower in Fort Stevens State Park looks peacefully blue — gulls caw overhead, waves lap against the rocky breakwater, and a pod of gray whales spy-hop and spray offshore. In calm conditions, the mouth of the most powerful waterway on the West Coast doesn’t seem to match its ominous nickname: the “Graveyard of the Pacific.” But the Columbia is one fickle river.

“A ship can come in in nice weather. They may be here for a week, loading and discharging. By the time they’re on their way out, the weather will have completely changed,” says Captain Mark Hails of the Columbia River Bar Pilots, a company of a dozen-plus shipmasters based in the storied seaport of Astoria.

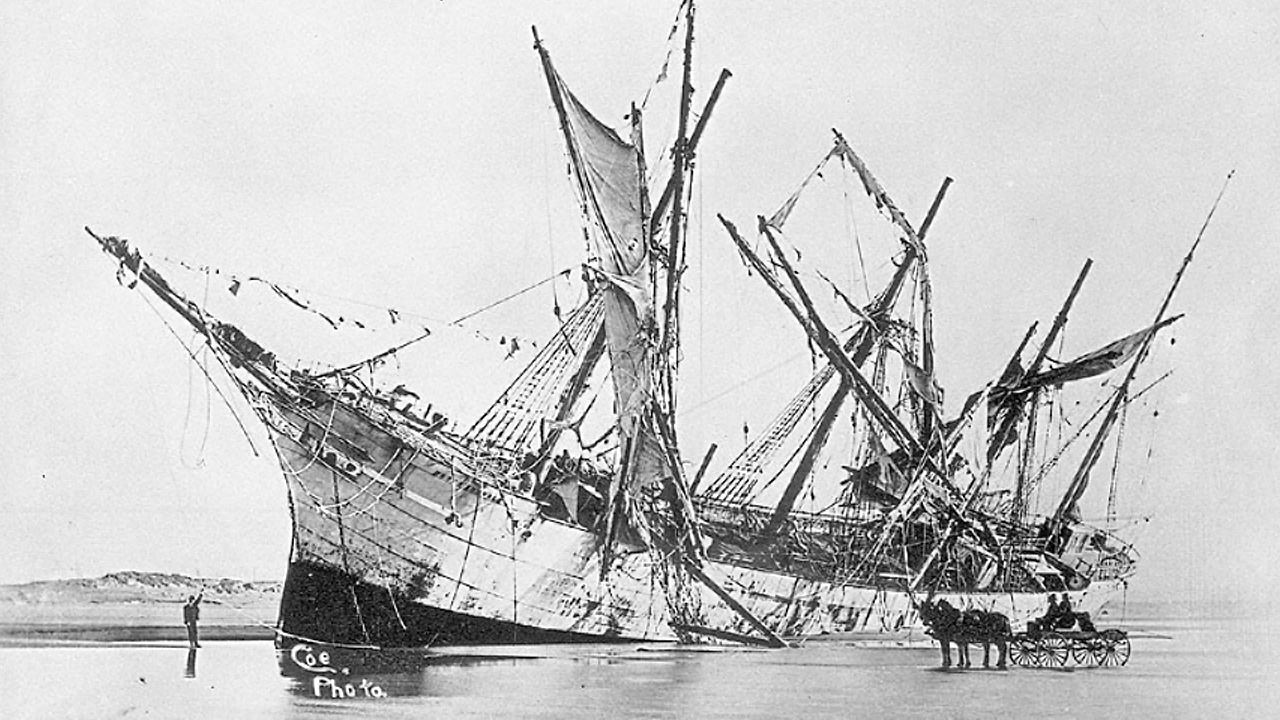

Like nautical valets, bar pilots have steered vessels in and out of the river since 1846 with one mission in mind: keeping ships from turning into shipwrecks. And it’s no easy task. Over the past three centuries, thousands of ships have wrecked off the Oregon Coast, which has a maritime reputation not too unlike the infamous Bermuda Triangle.

“The state archaeologist said there are over 3,000 known wrecks in Oregon waters, and he really only has data on about 300 of those,” says Chris Dewey, president of the volunteer-run Maritime Archaeological Society based in Astoria.

About 4 miles south of the South Jetty Observation Tower, I meet Dewey on a sandy beach along Clatsop Spit. Many vessels have run ashore here, such as the General Warren paddle steamer, the three-masted Leonese and the luxury schooner J.C. Cousins. But the most visible sign of Oregon’s dramatic history of shipwrecks is the ghostly Peter Iredale, a four-masted English ship that a heavy squall grounded in 1906. Beachgoers and photographers circle the ribs of the ship that rust away year after year. Its accessibility makes the Iredale one of the most popular spots in Fort Stevens State Park.

One of the few professional marine archaeologists in the Pacific Northwest, Dewey and his team of volunteers help regional heritage organizations and the state government research shipwreck sites that remain mysteries. The lion’s share of Oregon’s wrecks hide beneath layers of sand and decay in salty ocean water, where some form artificial reefs. Occasionally the hull of a wreck may resurface when a winter storm erodes a beach.

“There’s a lot of information out there to be had, and all of that is history of our culture,” Dewey tells me. “It’s really not been tapped by anyone in our area.”

Crossing the Bar

So many vessels have met their fate here at the jaws of the mighty Columbia. What makes this one of the deadliest stretches of water in the world is the Columbia Bar, an ever-shifting system of sandy banks and shoals where the river rushes into the ocean. The fresh waters of the Columbia flowing into the turbulent Pacific can mean chaos even when the course looks clear, as rapidly moving sand makes the underwater geography of the bar unpredictable. And when storms surge, high-velocity winds blow in all directions and whip waves into an angry froth.

“The easiest way to envision it would be the equivalent of two locomotives coming together head on. You can expect the force of ocean swells to increase by about 50 percent,” Hails tells me. “It can take the most seasoned sailors by surprise.”

Up until the 1960s, pilots would brave nasty Northwest storms in a mere rowboat — oaring out to inbound ships and boarding by climbing up a rope ladder. A 90-foot-long ship dubbed the Peacock made the journey across these choppy waters somewhat safer; the diesel-powered, round-bottomed boat had a smaller “daughter boat” mounted to its stern. Today pilots more often take to the skies in a helicopter, zipping 15 minutes from the Astoria airport to the ocean, where pilots get dropped onto the deck of the ship. It’s still a dangerous job, even for this expert crew of pilots.

With all the potential for devastation, why have sailors braved such forces to cross the bar again and again? The answer lies in the cultural and economic significance of the Columbia, a river that defined the livelihoods of the people living along its banks long before the arrival of European colonists. Today the river ranks among the most important transport systems reaching the Pacific Rim, connecting the local region to foreign markets that amount to nearly $25 billion in trade annually. It’s one of the continent’s major arteries for trade, especially for agriculture products.

It’s hard to visualize the scale of the Columbia as an import and export gateway until you stand on the bridge of a ship that’s larger than a football field and watch as a pilot masterfully steers it across the bar. That’s precisely what I did on a recent overcast afternoon. I pulled on a harness, jumped in a helicopter with Captain Joe Brady and repelled onto the deck of the inbound Panagia Thalassini, a 600-foot-long oil tanker flying the flag of Cyprus.

With speckled clouds overhead and a light mist blowing off the ocean, the views from the bridge looked moody and quiet as Captain Brady monitored sensors and eyed digital control panels. As he carefully drove the Panagia past the Cape of Disappointment, I could only imagine the nail-biting pressure of piloting this vessel into the mouth of the river when winter storms see waves swell to more than 15 feet.

It’s put a shiver in the spine of sailors the world over for hundreds of years.

Hunting for History

The most tragic episodes in the Oregon Coast’s maritime history predate the mid-20th century. That has a lot to do with a series of engineering marvels that have altered the flow of the river.

While onboard the Panagia, I peered out at the system of three jetties that the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers constructed between 1885 and 1939. These enormous rubble mounds stretch out for hundreds of yards like long fingers, totaling nearly 10 miles when added together. They deserve credit for making the Columbia Bar more navigable and easier to upkeep. Before the jetties came on the scene, incoming ships sometimes waited weeks for favorable conditions. That’s rarely the case these days because the jetties act like a spout, increasing the speed of the currents and pushing sediment farther away from the mouth of the river.

The jetties have lessened the likelihood of modern-day shipwrecks, but they have not eliminated the risks of venturing into the Graveyard of the Pacific. Nor have they diminished the enduring intrigue of shipwreck history.

“Because we have skilled and qualified pilots who make transiting the river safer today doesn’t mean that the danger is gone — it just means that we’ve learned how to cope with it,” says Jeff Smith, curator of the Columbia River Maritime Museum.

When visitors walk into the museum, the approximate site of many historic shipwrecks dot a massive map, each pinpoint representing heroic tales of nature versus humanity. Located along the Astoria Riverwalk, the waterfront museum has earned national attention for the scope of its collection, which includes shipwreck artifacts on display and even more in the archives. Smith took me on a behind-the-scenes tour of the private archives; rows of shelves hold a menagerie of relics such as lumps of beeswax from the mysterious wreck of a Spanish galleon that dates back to around 1700.

What’s not in the archives? Chests of treasure. “Quite honestly, most of the shipwrecks don’t involve treasure,” Smith admits. “The reason that we’re interested in them is because it’s part of the historical record, and we want to get that record as accurate as possible.”

That’s why the museum opens the doors of its research library to Dewey and his Maritime Archaeological Society, where the troupe of pros and enthusiasts conducts research on undocumented wrecks such as the yet-to-be-identified location of the beeswax galleon. Afterward, the maritime archaeologists continue the shipwreck conversation at the pub — specifically Buoy Beer Company.

“We go down to Buoy all the time, and there’s bound to be somebody who overhears us and says, ‘I’m going to go find a shipwreck, and I’m going to keep the treasure,’” Dewey smirks. “I’ll have to explain to him that there’s probably not treasure and that the law says he couldn’t even keep it if he found it. He probably won’t buy me another beer after I tell him that.”

Experience Oregon’s Shipwrecks

Maritime heritage soaks Oregon’s North Coast — something that’s even reflected in the names of iconic places such as Cannon Beach, named for the USS Shark that washed ashore near Arch Cape in 1846. Astoria’s Columbia River Maritime Museum’s collection exceeds 30,000 objects, including cannons from the Shark and artifacts from other wrecked vessels. Shipwreck enthusiasts can spend hours there diving into the seafaring history of the Pacific Northwest. The Tillamook County Pioneer Museum in Tillamook displays a small but compelling collection of shipwreck artifacts. The Maritime Archaeological Society occasionally hosts lectures and events open to visitors, and wannabe shipwreck sleuths can apply to become a member; their small network of volunteers includes members throughout Oregon, Washington and Hawaii. And to actually touch a shipwreck, visit the beach in Fort Stevens State Park ($5 parking pass required) at low tide, when you can walk up to the remains of the Peter Iredale.