It is an idea as old as society itself: From the Garden of Eden to Burning Man and beyond, we have always wondered how we might build a better society. But what if you could design your own utopia? What would that look like?

Over the last half century in the West, many have attempted to create their own ideal communities. Some have focused on scientific discovery—such as the eight “Biospherians” who sealed themselves in glass domes. Others, such as the Rajneesh, sought spiritual freedom in what they perceived as the wide-open West. From celebrations of art to back-to-the-land communes, people have explored numerous ways to forge their own path.

“Imagine a World,” a new, interactive exhibit at the High Desert Museum in Bend, now brings that question to life with art, artifacts and advanced technology that explore the past and literally invite you to create your own version of paradise.

“One of our big goals was to spark dialogue and to ask questions and get visitors thinking about what kind of community and society they would like to see and to be a part of creating,” says Laura Ferguson, Ph.D., the museum’s senior curator of Western history. “It’s about questioning the way things have always been done.”

The exhibit, which opens Jan. 29, 2022 and runs through Sept. 25, 2022, examines a number of communities to learn about their intentions and outcomes. The goal of the High Desert exhibit is neither to glorify nor to romanticize these attempts but rather to provoke questions about society and how we define it. “It’s equally meant not to condemn them either,” Ferguson says.

All in all, count on spending at least half an hour at the exhibit — it’s family friendly — before catching the museum’s free interpretive talks on otters and raptors.

Wild, Wild Country Explored

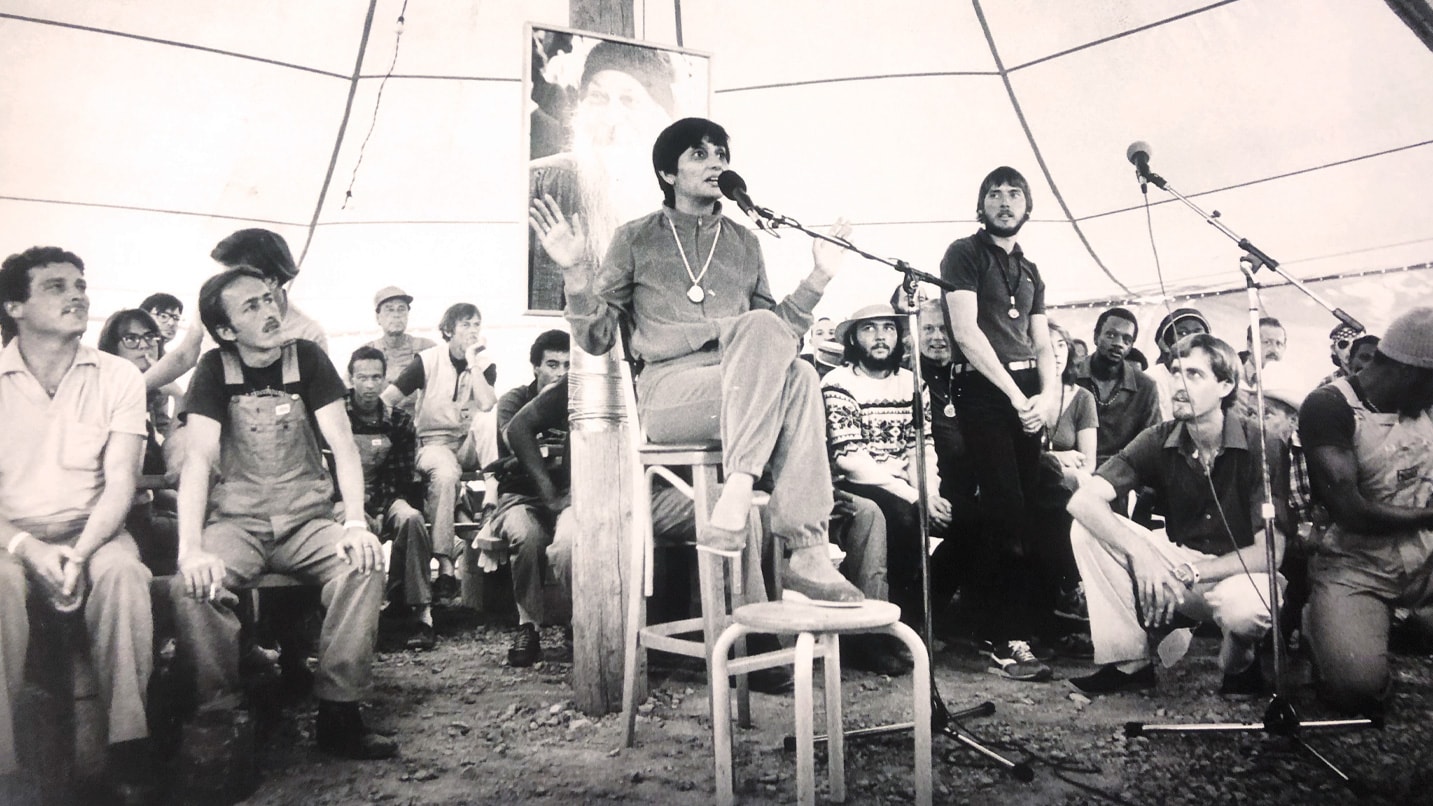

The idea for the museum’s utopia exhibit began as Oregon approached the 40th anniversary of the arrival in 1981 of the Rajneeshees in Wasco County. India-born religious leader Bagwan Shree Rajneesh and his followers sought to build a new society where wealth was not anathema to spirituality. They soon constructed a town of 7,000 people near the Eastern Oregon hamlet of Antelope, complete with an airstrip, restaurants and a post office. The new arrivals quickly realized their vision conflicted with reality, and the blank slate of the desert they had imagined was home to others who had laws and customs that didn’t mesh with the Rajneesh idea of utopia. That story became the focus of the Netflix documentary Wild Wild Country.

The High Desert’s “Imagine a World” exhibit explores this period of High Desert history with artifacts from both local residents and the “sannyasins,” as the followers called themselves. One of the first items you’ll see is a Rolls Royce similar to one of the 93 or so that the Bhagwan amassed thanks to donations from his supporters.

The scope of the exhibit quickly evolved beyond Rajneeshpuram and toward the broader concept of utopias, Ferguson says. Doing so encourages visitors to consider the lasting lessons of reimagining community.

“A key point is to think about how we measure success,” she says. “Rather than focusing on longevity, we might instead ask questions about how well they met their members’ needs and how some of the ideas that originated with these communities are still circulating today.”

Embracing Creativity

In a way, the utopias offer windows into the hopes and fears of a particular time. Many of the ideas sprang out of America’s post-war periods, when some embraced a “back to the land” mentality in response to the sense of a growing environmental crisis. A common theme among these intentional communities is how they offer different solutions to the problems they see around them and the difficulties they face.

The exhibit explores these ideas by looking at artist communes where embracing creativity and art was the focus of daily life. It includes a “zonohedron,” a geodesic-like dwelling that artists lived in at Drop City, which was formed outside of Trinidad, Colorado, in the 1960s. The dome isn’t an original but rather one built specifically for the museum by Drop City founder Clark Richert, a Colorado-based artist now in his 80s, who yearned to get art out of galleries and into the world.

Other artifacts and panels look at communities like Arcosanti, a community outside Phoenix that reimagines urbanism by blending architecture and ecology (or “arcology”), and Earthship Biotecture, a neighborhood in northern New Mexico centered around upcycling trash, like tires and glass bottles, into building materials for homes with minimal impact on the natural environment.

The exhibit also highlights work by Native American artists and filmmakers who imagine worlds where Native people are thriving throughout space and time, a movement known as Indigenous futurisms. By claiming the future, they dismantle narratives that have sought to erase Native people. The Klamath Tribes artist Camas Logue has two works in the exhibit, while Frank Buffalo Hyde, a painter of Nez Perce and Onondaga heritage, is creating work for the exhibition.

A glass wall installed inside the museum’s “Spirit of the West” gallery gives visitors the sense of peering into Arizona’s Biosphere 2, the largest vivarium ever built, where eight people famously lived among artificial biomes in the 1990s for years in an attempt to replicate what it might be like to colonize another planet.

The end of the exhibit’s path includes a reflection space that offers visitors a chance to visualize their own idea of a utopia. You can punch your idea into an interface that will then project your vision on an immersive screen around you. Peaceful beach? The Oregon Coast might appear. A diverse and equitable community on the top of Mount Hood? A sea of abstract faces might arise over Oregon’s tallest peak. You can even imagine a world in which it rains doughnuts every Sunday morning.

“You can definitely imagine that,” Ferguson says. “It’s pretty amazing.”