Of the many treasures washed to shore on Oregon’s North Coast — a stretch of cliffs and sand known as the “Graveyard of the Pacific” for its shipwrecks — one created quite a buzz in 2022. No, not the gold and jewelry discovered on the lost ship in “The Goonies.” We’re talking beeswax, and a ship carrying a load of it in its cargo hold that wrecked in 1693.

In June 2022, a team of investigators uncovered even more about the origins — and continuing mystery — of the storied ship known as “the beeswax wreck.” Timbers believed to be part of this wreck were retrieved along the rugged shore off the Nehalem Spit near Manzanita. Here’s the intriguing backstory about the wreck and how to visit locations of famous shipwrecks on Oregon shores.

A Manila Galleon and Beeswax Cargo

The site has long been an area explored by those seeking answers. For generations hunks of beeswax have surfaced in the sands surrounding Nehalem Spit. Oral history from the Nehalem-Tillamook and Clatsop tribes and journals of Lewis and Clark’s Corps of Discovery expedition document the presence of wax for hundreds of years. In fact, this lost galleon has raised so much curiosity, it actually inspired the ship from “The Goonies.”

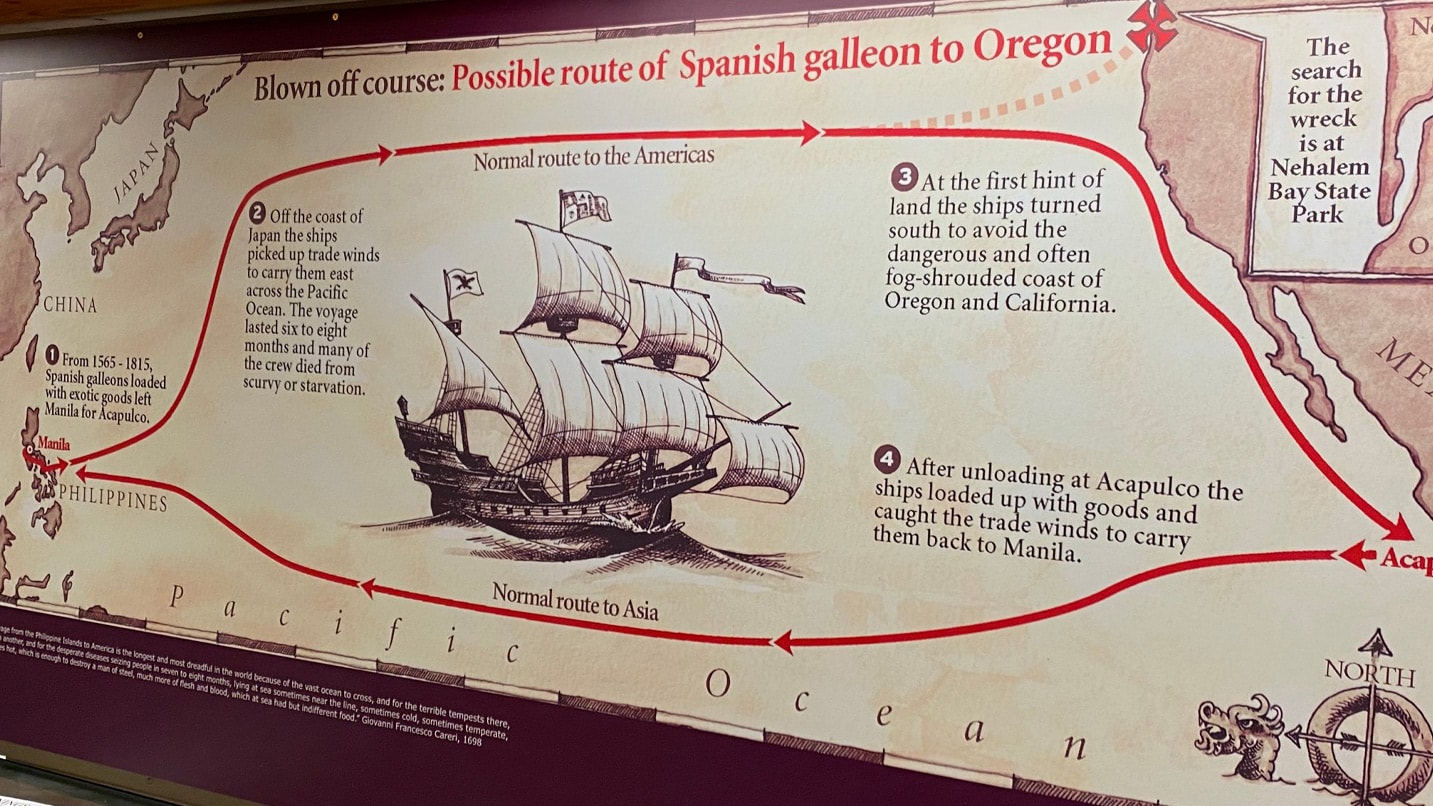

New research indicates that the beeswax cargo came from the Santo Cristo de Burgos, a 17th-century galleon (sailing ship) owned by the kingdom of Spain. Researchers determined the ship was built in Manila, in the Philippines, and carried luxury goods from Asia like Chinese silks and porcelain on the Spanish trade routes. For 250 years, ships traveled from Manila to Acapulco, Mexico — a journey of over 12,000 miles — every year.

Another important cargo on the Santo Cristo was beeswax. This may seem odd, but since the Catholic church deemed only beeswax appropriate for liturgical candles and no native honeybees existed to produce wax in the Americas, it was a hot commodity for missions or private chapels. Cut in heavy blocks and carved with the shippers’ identification marks, the beeswax served as not only trade goods but ballast to help keep the ship stable.

Because the Spanish kept excellent trade records, researchers determined that of the few ships that were lost without a trace, only two possible candidates could be the beeswax wreck, one lost in 1705 and the Santo Cristo, lost 12 years earlier. Due to where beeswax has been found — buried deep in sand and well above the high-tide line and into the river valleys east of Nehalem Bay — it was determined that only a tsunami could have strewn the cargo in such a pattern. This meant the wreck had to have happened prior to the devastating Great Cascadia earthquake and tsunami of 1700. Only one ship fit the bill: the Santo Cristo.

New Discovery of Timbers Near Manzanita

A couple of years ago, a local fisherman, Craig Andes, happened upon the ancient timbers in a remote sea cave in the Nehalem Bay area. Several factors inhibited the search until June 2022, when he joined a team of archaeologists and water rescue experts from Nehalem Bay Fire District to recover as much as they could. On June 16, 2022, during a very low tide, they carefully extracted several timbers from sea caves near Nehalem Spit that are usually flooded with water.

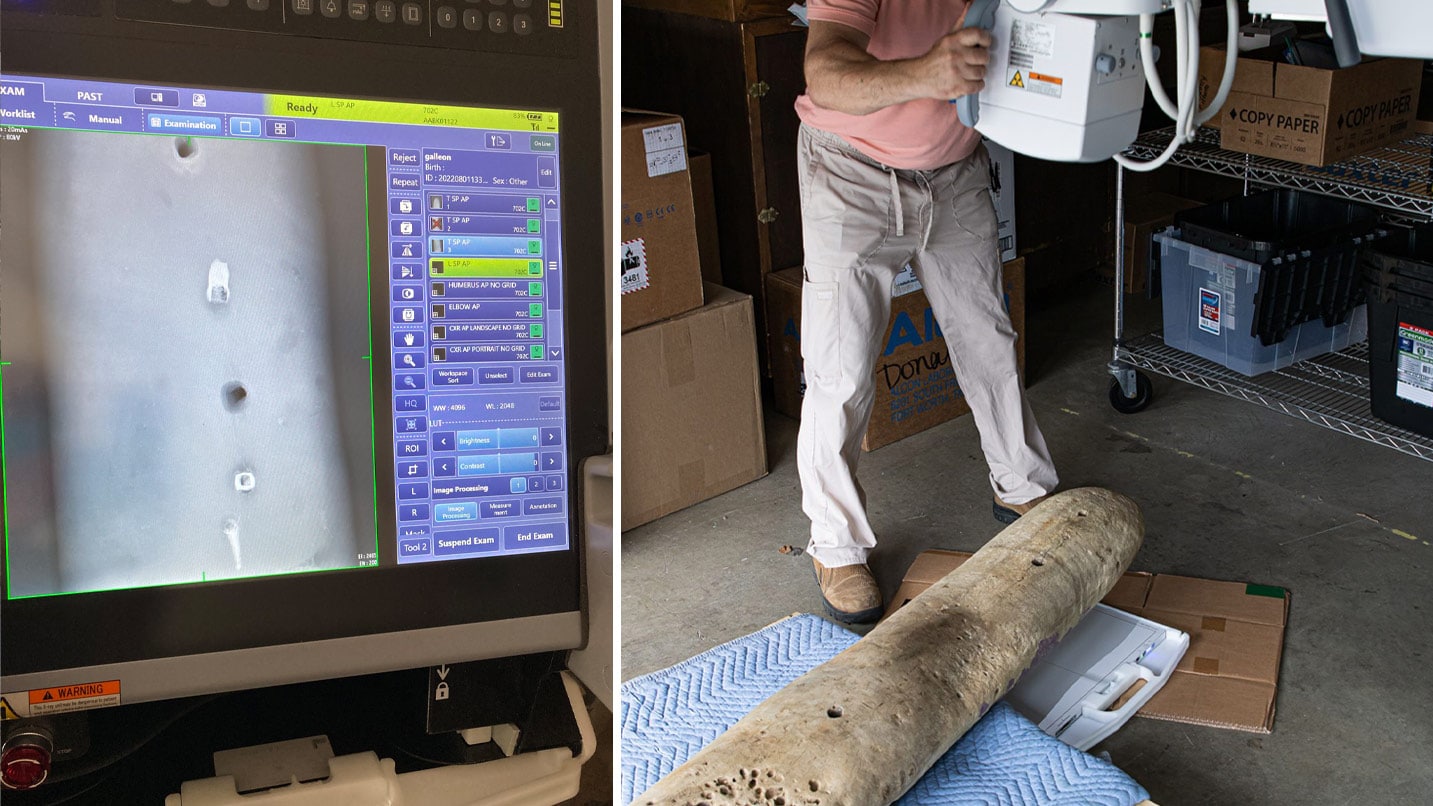

Removing multiple large pieces of wood — the longest of which was about 7 feet long — from that dangerous area was hazardous, even at low tide. “They only had about 40 minutes,” says curator Jeff Smith of the Columbia River Maritime Museum. Around 300 pounds of wet wood were recovered, some underwater and wedged in rocks.

Once the timbers were safely in Astoria in the museum’s research facility, the team began its investigation. With tracks from teredo worms — which burrow through saltwater-soaked wood — and patches of algal growth where it was exposed to the elements, the weather-beaten wood is still in remarkably good shape. The interior shows the wood is a beautiful golden color, “like tiger’s-eye agate,” Smith reports.

Multiple core samples about the size of a pencil eraser were taken and sent to labs in Seattle and the Philippines for carbon dating and species identification. The hope was that the wood samples would prove they were from a ship crafted in Manila at the time, and made of teak or other tropical species native to the Philippines.

Creative researchers also relied on an unlikely source — a local hospital’s mobile X-ray machine — to discover areas where metal spikes were (and some remain) deeply embedded in the wood. Smith theorizes the attachments could indicate some of the “ribs or outer and inner planking attached to beams.”

In November 2022, the wood samples came back with promising results. According to Smith, the wood appears to be “a Philippine hardwood called molave, known to have been used in constructing the Manila galleons.” He also notes that carbon dating of the timbers fits the timeframe for the Santo Cristo. This evidence adds weight to the theory that researchers have identified this legendary shipwreck.

Where to Learn More About Shipwrecks

The Columbia River Maritime Museum has an extensive exhibit about shipwrecks on the Oregon Coast, including an alcove dedicated to the beeswax wreck. Currently, visitors can examine a large piece of beeswax from the ship marked with Spanish shipping symbols, a wooden rigging block and blue-and-white Chinese porcelain sherds dated to the late 17th century. According to Smith, future plans include installing a roughly 3-foot, historically accurate model of the Santo Cristo and pieces of wood retrieved from the Nehalem Spit expedition.

In the same exhibit, visitors can also check out a metal sheet once part of the Exxon Valdez and two small cannons believed to be from the same ship as the one for which Cannon Beach is named.

If you’re headed to Manzanita or Tillamook, both the Nehalem Valley Historical Society and Tillamook County Pioneer Museum currently have exhibits on the beeswax wreck and other shipwrecks, featuring several impressive pieces of beeswax found by residents and other artifacts found in the vicinity of the believed wreck site.

Visiting Shipwreck Sites on the Oregon Coast

Ambling along the beaches or rivers on the Oregon Coast, you can easily imagine terrible storms or treacherous passages that might have meant the end for massive ships navigating the waters hundreds of years ago. Cross the dunes and walk along the shore of Nehalem Bay at Nehalem Bay State Park, where it is believed the Santo Cristo sank. In the Astoria area, gaze out to the west while crossing the Astoria-Megler Bridge at low tide and see the flats of Desdemona Sands, named after a ship that ran aground in 1857.

For the best chance at glimpses of shipwrecks, aim to visit these places when the tides are at their lowest. At Fort Stevens State Park in nearby Warrenton, the looming steel hull of the 275-foot Peter Iredale still attracts visitors who marvel at the shape and size of the 1906 shipwreck, visible at all tide levels. South of Depoe Bay, Boiler Bay is named for a massive ship boiler — only visible at extreme low tides — that once fueled the schooner the J. Marhoffer, until disaster struck in 1910. Other wrecks are visible occasionally after severe storms, including the sailing vessel Emily G. Reed near Rockaway Beach that met its demise in 1908, the schooner Bella near Florence’s South Jetty in 1906, and the steamship Sujameco that ran aground near Horsfall Beach in North Bend in 1929.

If you’re looking along these beaches, keep in mind that collection of artifacts deemed archaeological objects is illegal in many areas — even for small items like ceramic sherds — or requires special permits. Instead of collecting, admire the beauty and the history of this stretch of shore without disturbing it. While you’re out there, remember never turn your back to the ocean, and keep a lookout for sneaker waves, which can be deadly.

Smith says visitors can help with recovery efforts at a site like the Nehalem Spit by taking a photo of a found item left exactly in the place it was discovered and sending the photo to the museum. “You can walk that shore and know there’s a story,” he says, “and remnants of a Manila galleon somewhere out there that keeps giving us clues.”