For decades the Columbia River Maritime Museum has documented how the river and the Pacific Ocean have shaped life in Oregon’s Northwest corner, from deadly shipwrecks and Coast Guard rescues to the historic fishing industry.

In 25,400 square feet of exhibit space, however, only one case of materials served as a record of the local Native experience. The institution’s leaders recognized this needed to change. “We knew that was insufficient,” says museum curator Jeff Smith. “We knew that there was much more of a story to be told.”

In fall 2024 a long-term exhibition, “Cedar and Sea: The Maritime Culture of the Indigenous People of the Pacific Northwest Coast,” was completed to help tell the story. It highlights Native tribes that innovatively adapted to their climate by using what nature provided, as well as the ways in which their centuries-old traditions are carried out to this day. It’s one of the first and largest of its kind. Here’s what visitors should know about this groundbreaking display.

See Traditions Still Alive Today

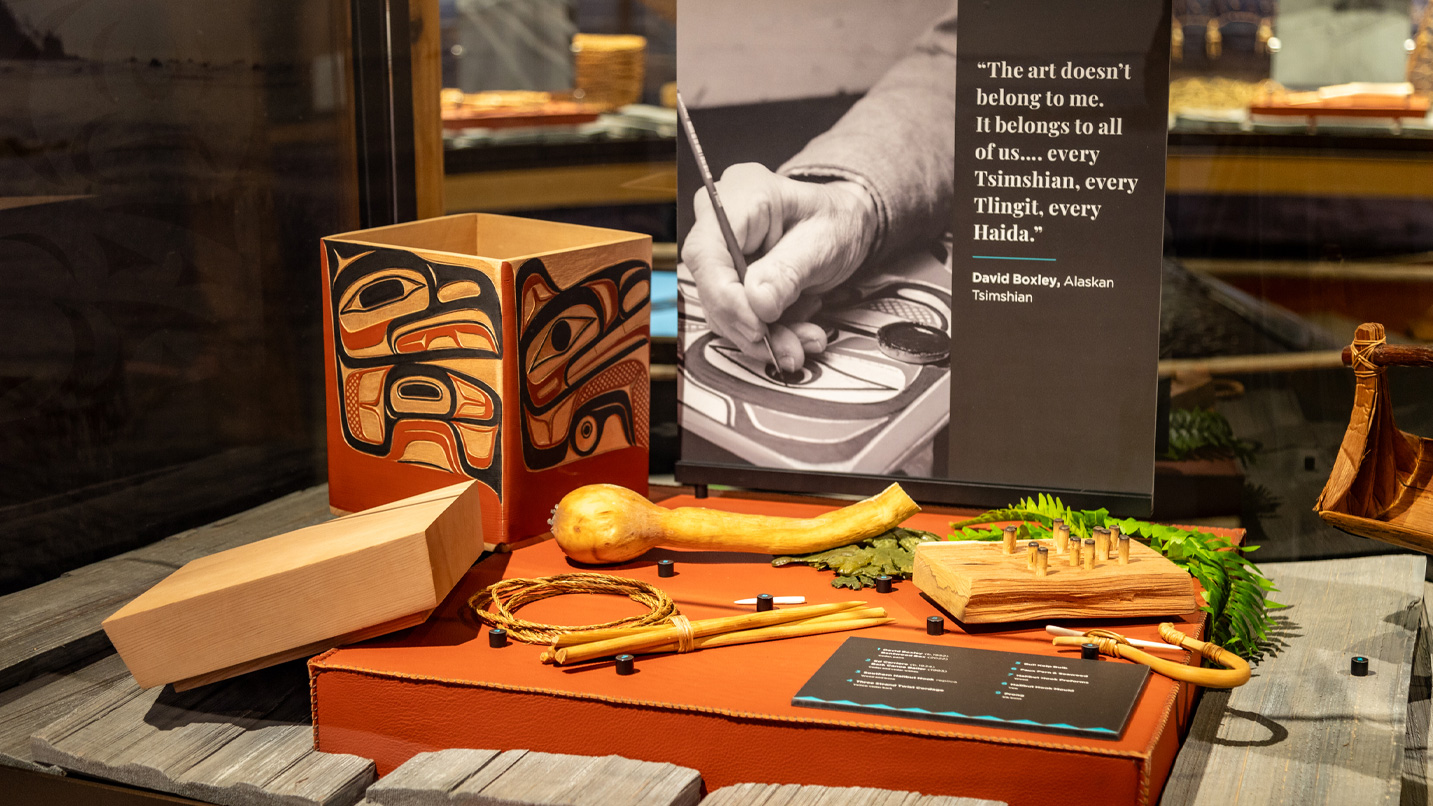

An ambitious undertaking that took four years to come to fruition, the exhibit focuses on the tools developed by Indigenous people who inhabited the region near Oregon’s North Coast. It honors coastal Indigenous communities that stretch from Yakutat, Alaska, to Southern Oregon, telling about the people through artifacts and stories contributed by tribal members. You’ll see a wide range of items from carving instruments to fishing gear to bits of shell and bone, but there are also stories and visuals that highlight the artistry behind the industry. Highlights include a 24-foot-long, hand-carved canoe and a striking mask of Kumugwe (god of the undersea) painted in bold shades of blue, red and white.

“I hope that people visiting this exhibit will be struck by the amazing ingenuity and skill that was required to develop this technology,” says Smith, “and, probably more importantly, realize that these people are still thriving, still carrying on their traditions and still living among us.”

Paying Tribute to Cedar, the Tree of Life

Despite the geographical range, one natural resource binds all of the tribes together: the revered western redcedar. The significance of the cedar comes to life throughout the exhibit.

When you walk into the exhibit, you may feel like you’ve slipped into an old-growth forest; the semicircular entrance features a floor-to-ceiling photo mural of dense woods along with a soundscape of cawing ravens and dripping water. Cedars were not only crucial when it came to facilitating life — every part of the tree was used for shelter, clothing, watertight baskets, smokehouses and more — the trees attained spiritual significance, becoming a cornerstone for these communities.

“Ancient people settled along the coastline because that’s where these massive cedar groves were,” says Smith. “It was that plant more than any other that provided them the means to develop a culture and thrive in this part of the world.”

In one room called the Gathering Basket, you’ll find the first of four Knowledge Giver videos that feature the stories behind the technology. Here Squamish and Stó꞉lo tribal member Cease Wyss leads a virtual field trip through a forest demonstrating the practice of bark gathering, surrounded by artifacts related to the revered tree.

The 20-foot-long Carvers’ Toolbox, which holds a collection of instruments used to whittle wood, serves as a timeline of carving as told through a cutting implement called an adze. It began as a stone with a sharpened edge lashed to a handle that then evolved into a tool with an ax-like blade. It’s used to this day by expert Native woodworkers like Nathan P. Jackson (Chilkoot-Tlingit), Karver Everson (Kwakwaka’wakw) and Joe Martin (Tla-o-qui-aht), whose dugout canoe greets you just past the exhibit’s entryway.

“All these people who are carving cedar, they’re using adzes that are based on early designs of their ancestors that go back thousands of generations,” says Smith. “They’ve just adapted them with modern material. That sense of continuity is what we’re trying to show.”

Harvesting the Bounty of the Sea

From cedars, the exhibit advances to the mighty Pacific Ocean, and how the sea shaped survival for these tribes. Here you’ll experience what it was like to live near the shore in ancient times through another immersive photo mural and an ocean-wave soundtrack, and a canoe and display case show off more tools of the trade. Two more videos detail techniques and traditional knowledge.

Lastly, visitors advance into a room devoted to an array of tools designed to harvest everything from fast-digging clams to strong-swimming salmon. Here you’ll see footage of a multigenerational fishing family in Metlakatla, Alaska, catching and then preserving their haul using traditional methods.

A Threatened Way of Life

“Cedar and Sea” may be a celebration of Northwest Indigenous practices, but it doubles as a reminder that those very practices face mounting existential threats. For instance, warming ocean temperatures stand to harm the wild-seafood market in states like Alaska, where many tribal members’ livelihoods depend on fishing. Metlakatla even lost its local fish-processing plant for five years — it only just reopened in 2024 — which made it difficult for Native anglers to get their product to consumers. Environmental factors also endanger old-growth cedar, which is increasingly difficult for Indigenous artists to come by.

“These organisms need a specific environment in order to thrive, and with the changes going on in our climate, it’s harder for these forests to continue,” says Smith, noting that tribes depend on resilience and adaptability to change technology and methods.

This is perhaps nowhere better demonstrated than with Suquamish master weaver Ed Carriere’s “Archaeology Basket,” whose layers replicate different patterns made across generations, illustrating how coiling advanced over the last 4,500 years. There may be change, but these cultures endure.

If You Go:

“Cedar and Sea” has no closing date at this time. Smith says that the museum will likely add artifacts to the collection over time, an incentive for guests to return and continue to learn.

During your visit, be sure to also make time to view “ntsayka ilíi ukuk – This Is Our Place,” a celebration of the Chinook Indian Nation, whose ancestral lands sit near the mouth of the Columbia River. The exhibit features nearly two dozen stunning photographs by Amiran White, a documentary photographer and award-winning photojournalist. Opened in mid-September 2024, it features a wide variety of images that illustrate the resiliency of the tribe, including vibrant public ceremonies and quieter moments.

The museum’s other exhibits are still on display as it gears up for expansion to be completed in 2026. You’ll still find plenty of videos and displays that demonstrate the risks of living near the Columbia River Bar, also known as the Graveyard of the Pacific. All galleries and the 3D theater are wheelchair-accessible, videos are accompanied by subtitles in four galleries, and verbal-description tours are available upon request.