Visitors to Pendleton today are instantly immersed in the Wild West through the rodeo culture and don’t even have to attend the Pendleton Round-Up to see it. On a walk through the charming downtown, a series of bronze statues depicts the Western pioneers of the town dating back more than 100 years. Some of these icons are Black, Native and women rodeo riders or heroes who’ve lent their skills, sacrificed their careers and even gave their lives as they paved the way for future generations. Here’s a guide to a few of these legendary heroes.

George Fletcher and the Infamous Saddle Bronc Ride

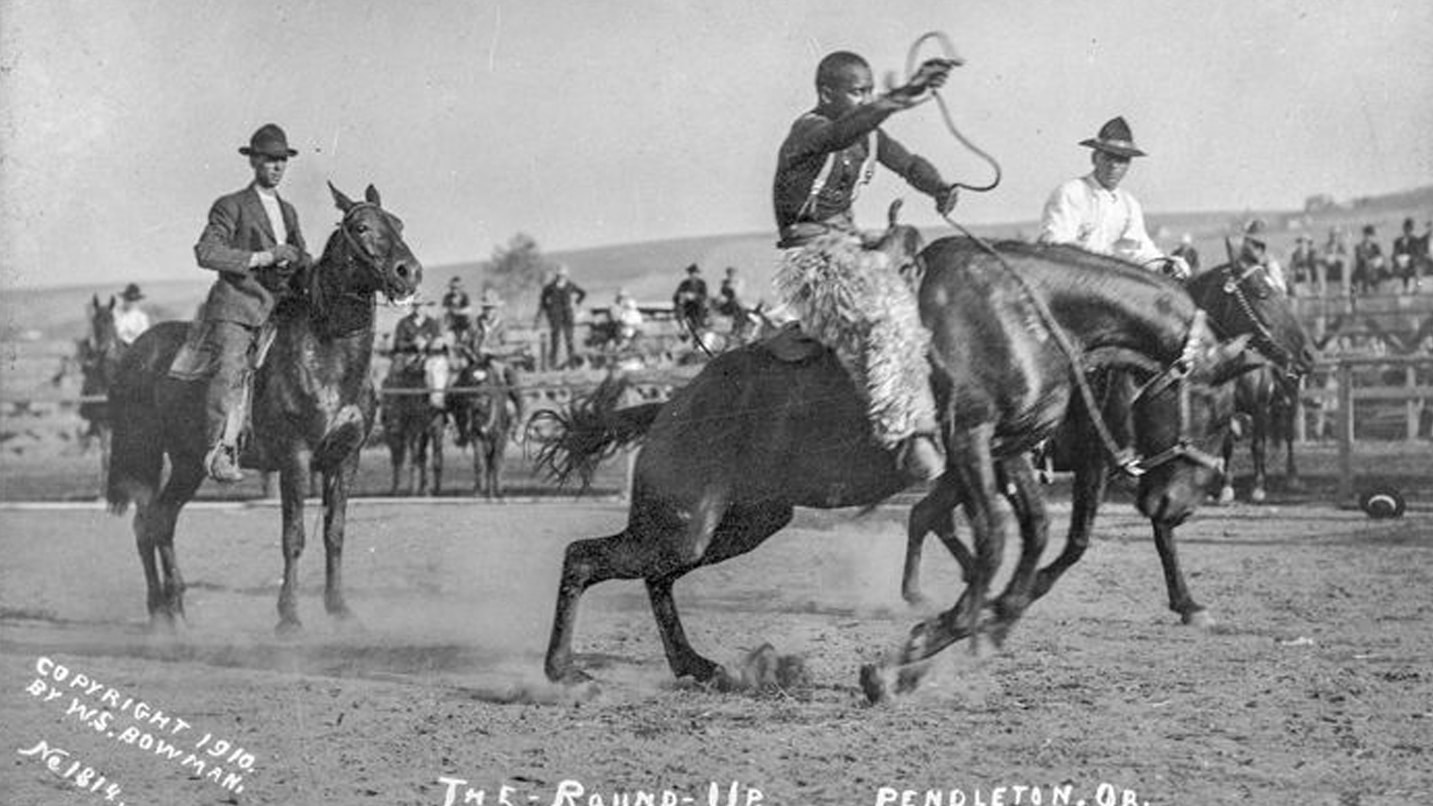

George Fletcher was one of the greatest Black rough-stock riders in the early days of rodeo. Raised in the Pendleton area, he spent his youth working horses on nearby ranches and on the Umatilla reservation until he entered his first rodeo at age 16. His actions would soon set in motion the conversation of race for cowboys in the sport of rodeo, paving the way for Black rodeo competitors for years to come. He’s most famous for the pivotal World Title saddle bronc-riding contest at the 1911 Pendleton Round-Up, his hometown rodeo.

Fletcher was pitted in the finals against John Spain, who was white, and Jackson Sundown, nephew of the Nez Perce Tribe’s Chief Joseph. Fletcher unquestionably made the best rides, according to the cheers of the crowd. However, the judges awarded first place to Spain, who with his brother Fred, had provided the rodeo stock for the first Pendleton Round-Up and had won the wild-horse race and stagecoach race in the Round-Up’s inaugural year the year before.

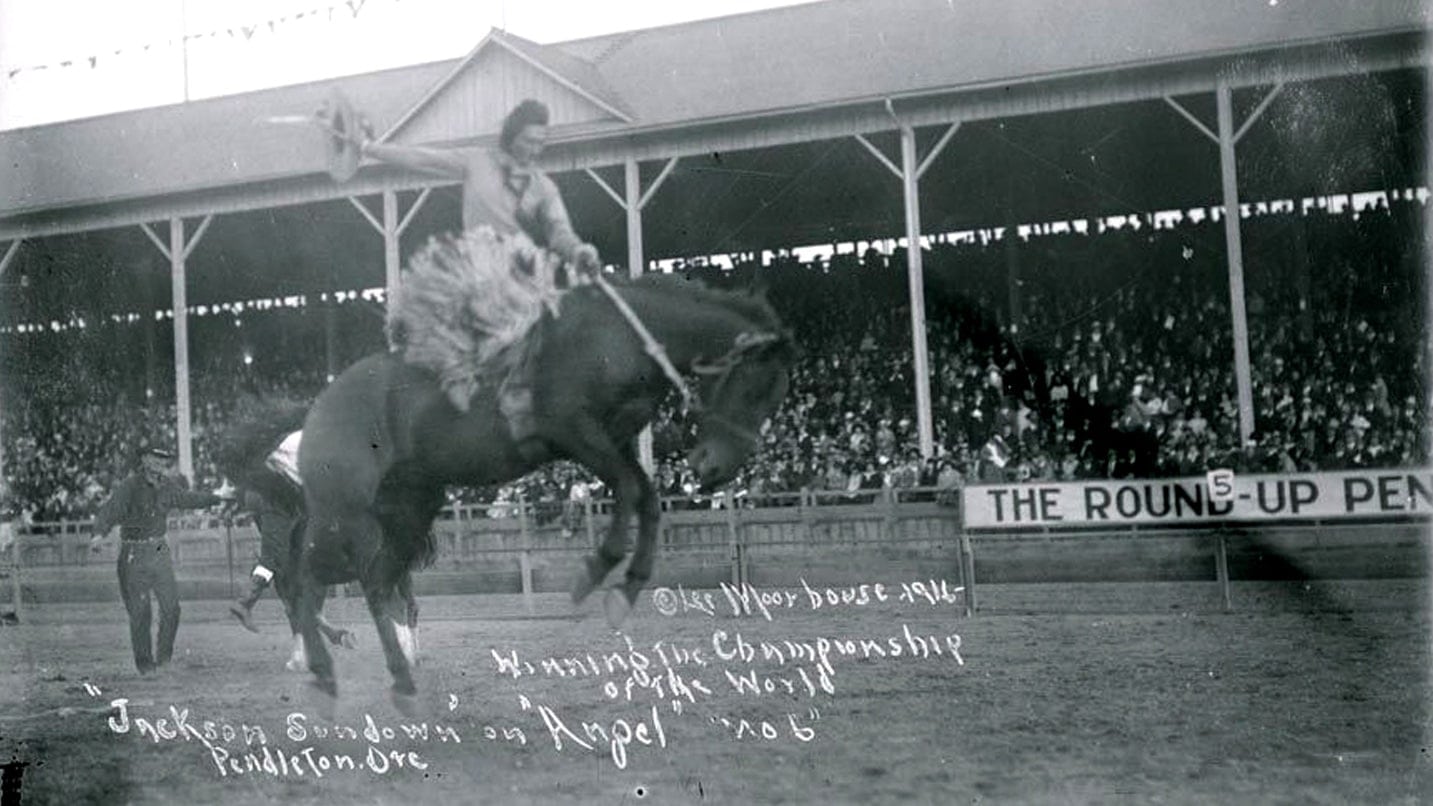

Second place went to Fletcher and third to Sundown. In an effort to “make it right” and placate the crowd, Sheriff Til Taylor grabbed Fletcher’s hat and tore it into pieces, selling it to the audience for $350 — enough to buy Fletcher a saddle like the one Spain had won. (Sundown would get his own redemption in 1916, when he became the first full-blooded Native American to win the Bronco Bucking Championship of the World at the age of 50, wearing his iconic white and black-spotted woolly chaps.)

Fletcher, meanwhile, went on to ride at local rodeos but not for competition — he was only allowed to ride for exhibition, without a chance at prizes or prize money. During World War I he served in an all-Black unit, then returned to Oregon to live the cowboy life he loved. In 1969 he became one of 10 people inducted into the first class of the Pendleton Round-Up Hall of Fame.

For more, visit the bronze statues of Fletcher and Sundown on Pendleton’s Main Street, part of the Pendleton Bronze Trail.

Also visit the brand-new George Fletcher mural in downtown Pendleton, at the Old West Federal Credit Union building on Main Street and SW 1st Street. It’s painted by Forest For the Trees artist Jeremy Nichols in partnership with Wildhorse Foundation, Pendleton Foundation Trust and City of Pendleton Arts Commission.

Bonnie McCarroll and a History of Women in Rodeo

Women were an active part of the Pendleton Round-Up’s early days — but that all came to a halt in 1929 after the tragic death of pioneer rider Bonnie McCarroll.

In the early days, McCarroll and other female riders were allowed to compete in the same events as men. “There were no restrictions, and cowgirls took advantage of that — displaying their athleticism, hijinx and outrageous costumes,” says Lynne McKee, a former cowgirl and a historian who manages the Benton County Fair & Rodeo. “Lots of ladies rode in the famous [Pendleton-made] Hamley & Co. saddles, too.”

McCarroll had enjoyed a career performing her saddle bronc-riding exhibitions and trick riding for kings, queens, dignitaries and countless rodeo fans around the world. She’s pictured in one of the most famous rodeo snapshots ever, taken as she’s being thrown from a bronc at the Pendleton Round-Up in 1915, her head inches from hitting the dirt. Despite the dangers that came with riding, McCarroll told her husband, Frank, in 1929 that she wanted one more ride at Pendleton before she hung up her saddle.

There was, however, one rule that women riders specifically had to follow. They were required to ride with their stirrups hobbled or tied together under the horse’s belly — supposedly to make it easier. McCarroll requested to ride unhobbled but was refused. (Some rodeos were moving away from this requirement at the time, but the rule was still in place in Pendleton.) This dangerous practice caused her to be helpless when her bronc, Black Cat, flipped over backward during competition, crushing her. She died nine days later.

After that tragedy, women were quickly pushed out of rodeo — specifically rough-stock events — for “their safety.” Some say it was an excuse to keep the women from beating the men in the rodeo events like McCarroll had often done. It took 70 years to bring women competitors back to the Pendleton Round-Up. In 2000 the Round-Up introduced the Green Mile — the largest pattern for professional women’s barrel racing. In 2018 the Round-Up added an all-ladies breakaway roping exhibition, a lightning-fast event that has paved the way for other large rodeos.

While there’s no bronze statue of McCarroll in Pendleton, you can hear more rodeo tales and dive into local culture during the annual “Get Wild in Pendleton” series of events on Saturdays between June and September each year.

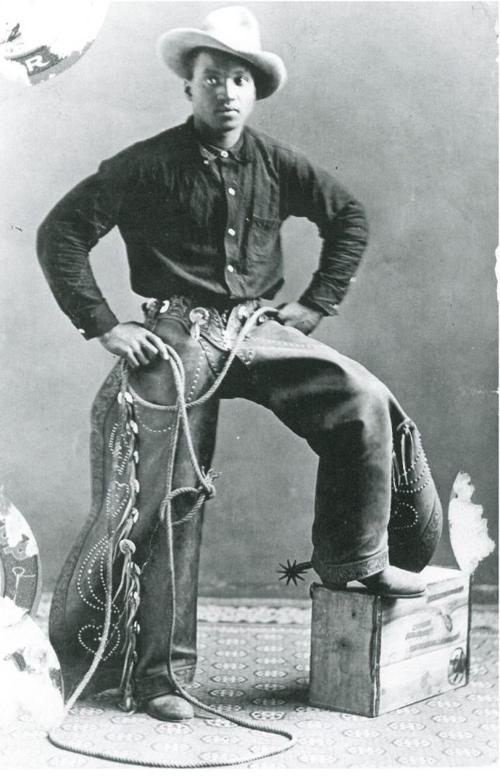

Jackson Sundown’s World Championship Victory

Born in 1863, Jackson Sundown Waaya-Tonah-Toesits-Kahn (Earth Left by the Setting Sun or Blanket of the Sun) was known from a young age for his athletic prowess and knack for great horsemanship. At the 1916 Pendleton Round-Up, he became the first Native American to win a Saddle Bronc World Championship, securing his place in history among both whites and Indigenous people to this day. Even before his victory, he led a remarkable life.

The nephew of legendary Chief Joseph, Sundown partook in many exploits as a Nez Perce warrior. He joined a small band of survivors hiding in Canada with Sitting Bull and those who defeated General George Custer at the Battle of Little Bighorn, as a war criminal for two years. He later moved back to the United States onto the Flathead reservation in northern Idaho, where he raised, bred, trained and sold horses.

Twice the age of his fellow competitors, Sundown began entering rodeos at the age of 40 in Canada and Idaho to earn extra money. A formidable competitor, he would win the bucking contests and the all-around titles at most of the rodeos he entered, making many of his competitors withdraw upon seeing his name on the day sheets.

Looking for a solution, the rodeo producers hired Sundown to perform as an exhibition instead. Sundown wore his signature sombrero over his Nez Perce pompadour with his long braids tied under his chin with a bright kerchief, and brightly colored shirts and large wooly angora chaps rounded out the look.

In both 1911 and 1915, Sundown found himself placing third in the Saddle Bronc Riding World Championships, hosted at the Pendleton Round-Up. Discouraged with third place, the 52-year-old Sundown decided to retire — but local sculptor Alexander Phimister Proctor, who was working on a likeness of Sundown, convinced him to enter again and paid his entry fees for the 1916 contest.

The championship win by Sundown and his bronc, Angel, was legendary. Fanning his iconic sombrero over the horse’s final jumps of the contest, the crowd of 10,000 roared its approval. Sundown died of pneumonia in 1923, but his legend lives on at the Pendleton Round-Up in his iconic bronze statue.

Oregon’s Black Lumberjacks Defied the Odds

Oregon joined the Union as the 33rd state and the first whites-only state: Black people were openly discouraged from migrating to the state in 1859. A small logging town located about two hours east of Pendleton ignored that rule and created a camp in 1923 known as Maxville. This was a booming timber town of evenly mixed Black and white residents who had been recruited by Bowman-Hicks Lumber Company of Missouri for work as loggers, despite state exclusion laws that discouraged people of color from living in Oregon.

In fact Maxville was the largest town in Wallowa County and the only town in the county to have Black citizens. Keep in mind that a prominent Ku Klux Klan leader, Walter Pierce, had recently been elected governor of Oregon. While racially mixed, Maxville was not racially integrated.

The town followed Jim Crow-style Southern laws with segregated housing, schools and baseball teams, but in the lumber yards, they worked side by side. Bowman-Hicks’ emphasis on a healthy work-life balance led the community to come together, and friendships flourished — even famously combining forces as the Maxville Wildcats baseball team to beat the local white teams of Elgin, Joseph, Enterprise, Wallowa and La Grande. According to a newspaper article, the integrated team “played rings around the other team, scoring at will,” and pioneered the slogan “Friendships Say No” to Jim Crow — opposing their own town’s laws.

In 1933 Bowman-Hicks ceased production as the Great Depression caused the lumber market to plummet. Maxville was closed for good. Many Black families moved to local cities in Oregon and neighboring states in search of work. A blizzard in the 1940s destroyed much of what was left of the town, but the spirit and history is being preserved for visitors to explore at the Maxville Heritage Interpretive Center in Joseph.