If you’re like me, you’re bound to be curious when traveling the wide-open spaces of Oregon. I need to know everything I can.

That’s how it was when we headed south on US 97 searching for the forty million years of geologic history found in the Oregon state rock called “Thundereggs.” I cherished these magical, mysterious golf ball size rocks as a child for their drab exterior, but their oh-so-creamy and colorful agate interiors that continue to be trophy prizes for young and old rock hounds alike.

Technically a thunderegg is not a rock; it’s a nodule or a geode that forms inside other rocks. But if you were to judge by the throngs of visitors who stream through the Richardson’s Recreational Ranch just off US 97 near Madras, thundereggs are without question the most popular rock in Oregon.

The expansive seventeen-thousand-acre ranch allows rock hounds the opportunity to dig and discover countless secrets in the soil. On a recent visit to the ranch, Casey Richardson, co-manager of the expansive operation, led us across seven miles of bumpy back road to a mother lode akin to thunderegg heaven on Earth.

Casey Richardson’s family used to raise beef across their impressive spread, but decades ago they had a different idea. Now, Casey co-manages the family property – not for livestock, but for the dirt under-foot.

We arrived at the southern end of what is known as the “Blue Bed,” the oldest and most productive thunder egg site on the Richardson Ranch for the past four decades.

Casey said that here, it’s all about the gas — but not the kind you pump. “Thunder eggs are gas bubbles that formed in a rhyolite formation between thirty and forty million years ago,” noted Casey. He teasingly declared that all you need to make a thunder egg “is a volcano that produces lava rich in silica, the stuff of which quartz is made. As the lava cools, steam and gases trapped within the lava form bubbles. The beauty is in the bubbles.”

Armed with rock hammers, shovels, and insatiable appetites for the unexpected, Chris and I were anxious to do some digging in the dirt, and it didn’t take long to hit pay dirt. The technique isn’t too difficult: simply kneel down and hammer, scrape, chisel, and mine the dirt away from the egg.

“Rockhounds love to get dirty,” declared Casey. So bring a bucket, gloves and rock pick (Richardson’s provides a bucket and rock hammer for your use) to dig Oregon’s treasured state rock from the dirt.

Thundereggs became Oregon’s official State Rock in 1965. They can be as small as marbles but can reach basketball size. Filling a five-gallon bucket is no sweat and didn’t take us long; then the real fun began back at the rock shop. Casey’s lifetime of experience knew just the right angle to make a slice through one of our eggs with a diamond-embedded saw blade and reveal the rock’s interior.

Thundereggs were first discovered in this area during the 1920s by a rancher named Leslie Priday. For the past 40 years, the Richardson family has owned and operated its recreational rock ranch for eager tourists who can dig their own treasures or purchase them inside a small lapidary shop.

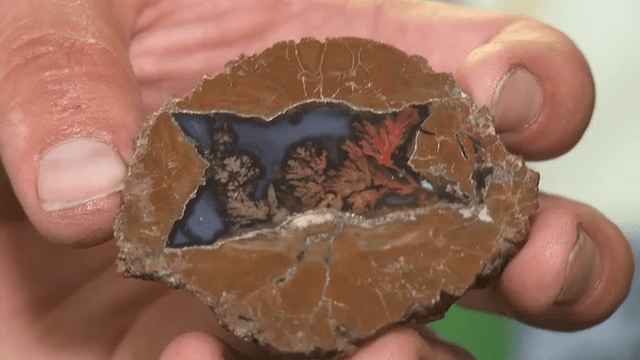

When they are cut open, they reveal agates of various colors and exquisite designs that stand out when they’re polished.

As we waited for the automated saw blade to slice open all of our prizes, Casey showed off his most valuable thunderegg, called a “Priday Plume.” He called it “one in a thousand” and it was easy to see what he meant for it looked fabulous with varied hues of blues, greens and reds.

Richardson’s displays inside the shop are real show-stoppers, with rows of gorgeous thundereggs and other exotic-looking rocks from across the world. You’ll discover that thunder eggs can be made into beautiful, varied jewelry, especially pendants, pen stands, and bookends.

Meanwhile, back in the work shop, Casey said it’s the surprise of it all that continues to excite him. Once a rock is cut open, each provides a lasting memory of time well spent in the Oregon outdoors. “The really neat part is that when you dig up a thunder egg and bring it down to have us cut it open, you’re the first person to have ever seen that rock. And to think it took sixty million years to make it, plus there’s no two alike, they’re all different, and the next one is going to be the very prettiest one you’ve ever cut.”

I discovered that the simple beauty and complexity of these geologic wonders are best appreciated when the egg is carefully cracked open and placed on display to reveal a moment from a distant past that’s been frozen in time. The sanding and polishing reveal depth and features that are beautiful and unique, just like the state that the rock represents.

“Everybody likes to get outdoors as a family and do something together,” said Casey Richardson. “Maybe you get a little dirty digging in the ground. But you get to take your prizes home, and a five-gallon bucket of thunder eggs only costs about twenty-five dollars. That’s not bad for a day together.”