Editor’s note: Walter Cole, Portland’s iconic drag queen known as Darcelle, died of natural causes on March 23, 2023 at age 92.

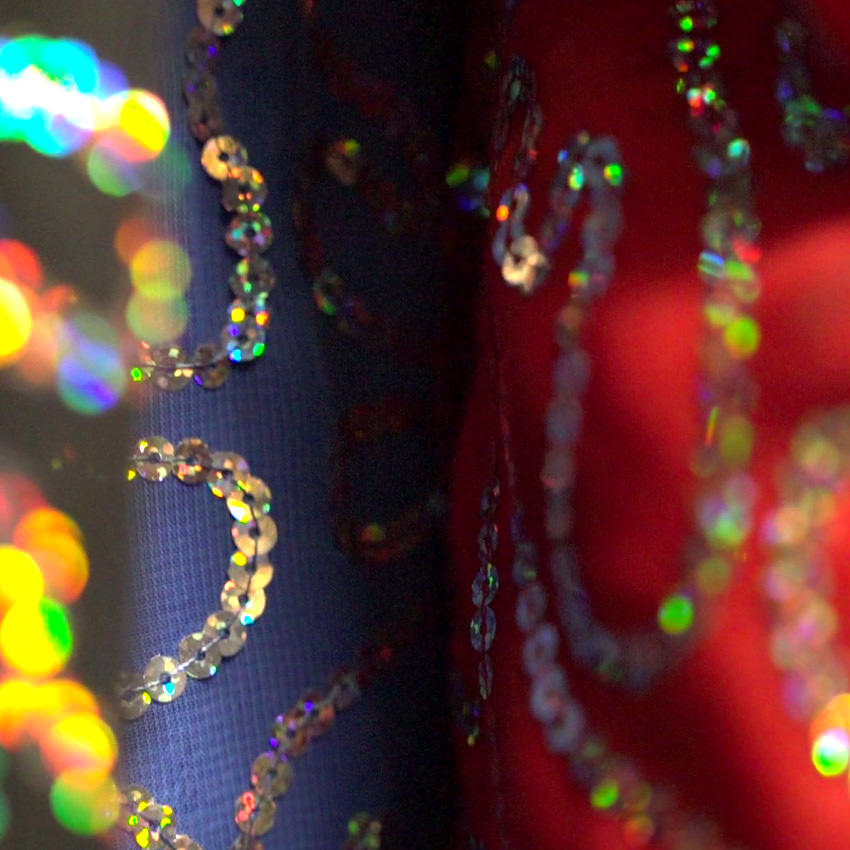

Every night before the first queen struts across the stage, the club’s flickering laser lights, hissing smoke machine and thumping diva anthems give audiences a glimpse of the campy kitsch that defines the West Coast’s most iconic drag revue.

Hosting the longest-running show of its kind, now in its 51st year, Portland’s Darcelle XV Showplace frequently sells out its weekend performances. Yet hardly anyone but the queens themselves have seen the venue’s true nerve center: a squeaky backstage staircase that spirals up from the dressing room in the basement, a passageway out of the glittery underworld.

Few get to witness this nail-biting opening act: Prior to stepping into the spotlight, queens gussy up in front of vanity mirrors and then quickly ascend the narrow stairs to the compact stage above — ducking to keep their wigs from smashing against a low ceiling and pulling gowns knee-high so as not to trip themselves. Many brave it all in vertigo-inducing stilettos, no less.

I tag along behind veteran Darcelle performer Kevin Cook as he climbs up to the stage for a preshow mic check. Better known by his drag name, Poison Waters, Cook wears a curvaceous neon dress with a flashy orange, pink and black camo pattern. His — or her when in costume — feathered headpiece brushes the wall with each seemingly choreographed step. He’s no stranger to this routine.

“I would imagine it’s kind of like you’re in a pirate ship and you’re down in the hole,” Cook says of the rickety stairs at the back of the showplace. “It’s not pleasant, but we do it in five-inch heels all night long. No one’s died yet, so I guess it’s OK,” he laughs, unfazed.

Sure, the staircase doesn’t command much attention on its own; instead, it’s the two distinct realms it bridges. In the basement, hundreds of Darcelle XV’s handmade outfits line racks — a visual compendium of the venue’s colorful history — and the night’s performers buzz along a wall of makeup stations, painting faces and primping hair. Above ground is the gender-bending limelight of the stage, where generations of drag queens have lip-synced their way through more than five decades of queer life. They did so at a time when police regularly raided LGBTQ bars, when drag was against the law, when cross-dressing could end in arrest.

Celebrating 30 years in drag, the man behind Poison Waters has seen his audiences grow as his art form has evolved — dancing in step as the LGBTQ liberation movement has plodded past triumphs and tragedies, always with sass and candor. Cook has watched much of it unfold from the stage at Darcelle, where he co-hosts the nightly show alongside the club’s prolific founder and namesake, Darcelle XV herself (aka Walter Cole).

Becoming a Queen

Chances are, anyone spending a night out in Portland will invariably encounter at least a few queens roaming the streets fully dressed in glamorous garb. Today the drag scene flourishes thanks in large part to the influence of trail-blazing queer figures such as Darcelle, who opened her club in 1967, two years before the Stonewall riots in New York City.

First-time visitors to the showplace might easily miss its historical significance in a contemporary context that sees drag queens sashaying further into mainstream pop culture.

But Cook remembers when queens would rarely, if ever, venture out of gay clubs wearing sequined dresses. Present-day Oregon may rank among the most equitable places in the nation for queer rights, such as being the first state allowing trans and genderqueer people to choose a nonbinary option on their driver’s licenses. This progress, however, did not come without its struggles. Oregon in the ’80s and ’90s saw more anti-LGBTQ ballot measures than any other state, culminating in the 2004 passage of an amendment to the state constitution that banned same-sex marriage. (Measure 36, as it’s known, was eventually overturned in 2014.)

“When I first started, it would never occur to me to get in drag and go somewhere,” Cook says. “I’d put my drag in a bag, go to the venue, get in drag, do my work, take it off and then go back out into the world.”

Portland queens would mostly reserve their snarky one-liners and Diana Ross impersonations for gay bars and Darcelle’s club — literal safe havens where many social outcasts and queer misfits could find a sense of kinship.

Born in Southern California, Cook and his family relocated to the Parkrose neighborhood of Northeast Portland in 1979. As a teenager in the ’80s, Cook would attend the infamous City Nightclub, a now-defunct all-ages LGBTQ venue in downtown Portland. While the venue had a fraught relationship with Portland police, who made it a frequent target, young patrons featured in a short 1996 MTV documentary described the club as a second home.

There at the City Nightclub, Cook first encountered a drag show. Every Saturday at midnight, the dance floor came to a standstill as a few drag queens took to the stage. At first Cook viewed the entire performances as an annoying intermission — he simply wanted the DJ to keep the music on so he could dance with his friends. But one night, a special drag show inspired him to, as Gloria Gaynor puts it, “see things from a different angle.”

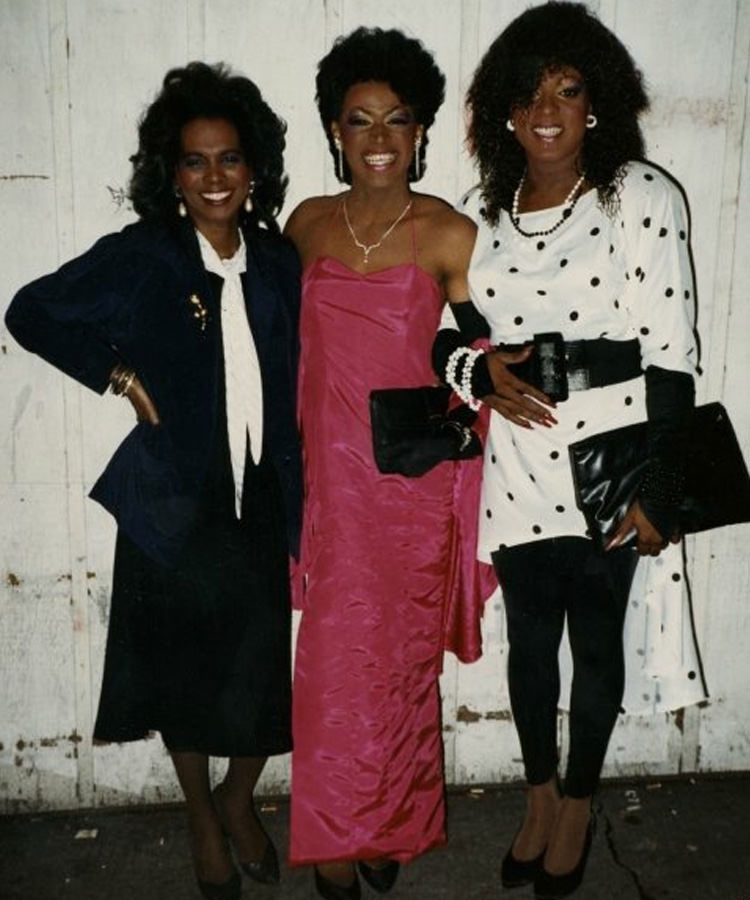

“I saw a great show that had special-guest entertainers … they were all black ladies — black drag queens and one trans woman,” Cook says. The troupe performed a revue of the musical “Dreamgirls.”

“That just changed everything for me, as far as drag queens onstage and enjoying what I was seeing. It just kind of occurred to me that I hadn’t seen anybody that I thought looked like me or had the same aesthetic as me.”

One of these queens went by the name Rosey Waters, and at the time, she frequently emceed events in Portland. This turned Cook into a Rosey Waters groupie, and he followed her around town. At one event, Rosey asked anyone in the audience if they wanted to be a drag queen. Cook’s hand shot up.

Rosey helped Cook shape his garishly glitzy drag persona. First she took him on a shopping spree for wigs, makeup and undergarments. Then Cook visited Rosey’s apartment in Southeast Portland for makeup tutorials, where she would paint half of his face and he would paint the other. Cook’s then-boyfriend made him a dress. Cook had found a drag family, so when he had to pick a name for his onstage character, he adopted Rosey’s surname; he chose “Poison,” on the other hand, because of the Christian Dior perfume.

Rebels in Heels

The resounding echo of applause at Cook’s first performance hooked him. Since that fateful debut, his fast-witted, say-it-like-it-is personality has kept him in demand in Portland and throughout the country.

Cook credits much of his success in building a decades-spanning career in drag to Darcelle, whom he describes as his mentor, friend, boss, neighbor and even landlord. Since 1989, when Darcelle encouraged him to march in Portland’s Pride parade, Cook has performed innumerable times in the legendary club, and he’s modeled the work ethic of Darcelle, whom the Guinness World Records crowned the world’s oldest drag performer. Cook and his partner even rent a bungalow from Darcelle that neighbors her own sprawling home in Northeast Portland.

Cook has also followed Darcelle’s lead in taking drag out of gay clubs. Long before RuPaul hosted his hit reality show, “RuPaul’s Drag Race,” queens like Darcelle were already performing in front of largely straight audiences that had rarely, if ever, seen a man wearing a dress in public — they hosted events, galas and fundraisers for a myriad of noble causes. Over the years, Cook has volunteered or worked with dozens of nonprofits and charities, including Cascade AIDS Project (CAP), where he has also served on the board of directors; the Women’s Intercommunity AIDS Resource; and CAP’s Camp KC, a summer camp he directs for children whose lives are affected by HIV/AIDS.

“Drag [queens have] always been the change makers,” Cook says, citing the lesser-known history that drag queens have played both in Portland’s queer history as well as LGBTQ life across the country: At the Stonewall riots, transgender people of color like Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera — self-described drag queens — led the fight for their rights at the front lines. Similarly in Portland, drag queens stepped up first during the HIV/AIDS epidemic to host fundraisers.“People look to drag queens because we easily grab attention,” Cook says. “People look to us and hear what we have to say because we’re the loud, visual ones.”

But it’s not Cook’s style to pin a “community leader” badge on his chest. “I really think it’s everyone’s responsibility to step up to the plate,” he says. “I think as long as I’m doing the right thing in my mind, hopefully people who are looking for a way will look the way I’m going and follow that.”

For contemporary performers and those whose fancy footwork graced stages long before, subversively toying with the rigid constructs of gender doubles as its own kind of activism. Drag, of course, challenges social conventions of masculinity and femininity. But historically, queens have also helped define a sense of belonging. And whatever room Cook enters, his welcoming, chameleon-like personality lightens the spirit of the crowd.

“I think if you say you’re in drag, well, then you’re in drag — you believe in your own truth,” he says. “So anybody can be in drag if that’s what they call it and that’s what they want it to be. Drag is theater — and it’s fun.”

I stand with Cook on the stage at Darcelle’s an hour before the doors open for “Catch a Rising Star,” his Tuesday night “open-mic” event that welcomes any queen of any skill. The tightly packed chairs sit empty in the small room. Yet I get a sense of the rush Cook still must feel when he steps out from behind the curtain, the warm applause from returning fans and newcomers alike.

“You’re in the chaos of the dressing room. Then we’re funneling up this horrific, terrible staircase and — boom — we all fall out of the curtain into the audience,” Cook tells me in his characteristically up-tempo fashion. “As soon as the lights hit us and we’re all onstage, it’s just magic.”

Experience Portland’s Drag Scene

A landmark on the national drag circuit, Darcelle XV Showplace’s nightly show (hosted Wednesday through Saturday year-round) has changed little since its inception. Cook refers to the style of drag he performs as “classic drag.” He regularly graces stages at Darcelle’s as well as other venues around the city (check Poison Waters’ calendar to see upcoming shows).

A world of drag: The increased popularity of the performance art has not only grown audiences but also exposed them to a wider spectrum of queens. “Now there’s literally a rainbow of what is called drag,” Cook says. “And if it’s drag, it’s here in Portland. There’s an audience for every kind of drag, and there’s a spotlight for every kind of drag.” All kinds of performers — both professional and amateur — appear onstage at the “open-mic” event “Catch a Rising Star,” which Cook hosts at the Showplace on Tuesday evenings (March through August).

Portland Pride Month: A great time to see the wide-ranging variety of Portland drag is during the annual Pride festivities in June, when drag queens march in the long-running Pride Northwest parade and appear in a whole range of special queer events hosted throughout the month. In late June, the family-friendly drag extravaganza Peacock in the Park takes over Washington Park and raises funds for LGBTQ scholarships.

Year-round events: Gay bars and a variety of other venues frequently host drag events such as CC Slaughters (every Sunday), Tonic Lounge (every Thursday) and the always packed Sunday morning drag brunch at STAG. Local and national drag acts provide entertainment at monthly LGBTQ-centric dance nights; notably, Blow Pony has frequently hosted “Drag Race” contestants at its fourth-Saturday, anything-goes club night at Bossanova Ballroom.

A note about etiquette: It’s expected that you tip drag queens during their performances, so come with a pocketful of dollar bills. When attending an event at an LGBTQ bar, show respect to both audiences and performers — touching anyone is certainly off limits, and avoid using offensive slurs or asking rude questions. Remember that these are queer spaces first and foremost.