I’m a big believer in exploring Oregon’s back roads and learning something new about my home state at the same time. There are many ways to explore Oregon’s back roads and byways and a growing favorite way to see the sights and hear the sounds of the state is by rolling on two wheels.

Winter’s cold and wet rarely slows down Sally Miller and Hannah Vaandering from putting in their training miles on the Banks-Vernonia State Trail in Washington County.

“Near Banks, much of the trail is pretty flat so you don’t worry about a lot of hill work,” noted Miller, a longtime cyclist. ”It’s nice that way so newcomers can get used to riding on their bikes or riding with a group of friends…it’s also safe because you are away from road traffic.”

The Banks-Vernonia Trail is made for cruising through a Northwest Oregon forest; plus, you can also enjoy 13 old railroad trestles that give you a flavor for the area’s history. There is a towering trestle at the Buxton Trailhead, where Oregon State park Ranger Steve Kruger, said “at 85 feet up in the air, you can really get a feel for the trail’s history.”

You see, a century ago this was a railroad line that moved big timber between nearby Vernonia and Portland. Kruger added that the trail is Oregon State Park’s first “Rails to Trails” conversion; it’s 21 miles of paved pathway with a gentle 2 to 5 percent grade.

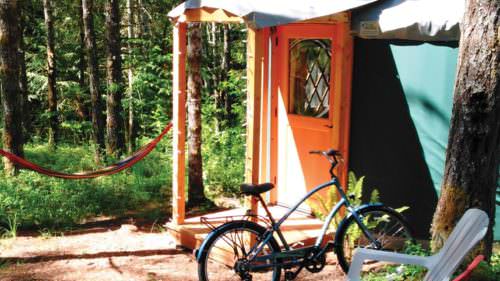

Visitors to the trail can also enjoy Stub Stewart State Park – in fact, you can’t miss it because the trail runs right through it. The park’s rental cabins make a winter time campout and trail riding a super way to combine cycling into a weekend getaway. You will find nearly all of the comforts of home inside each of 15 cozy and heated cabins that go for $43 a night.

You will also notice something new inside the parkland this winter: spectacular views to the coast range are getting better thanks to a new “forest restoration” project. Crews are selectively thinning dense stands of 30-year old Doug fir trees across 70 acres of the 1800-acre park. “We looked at the size of the trees and the health of the trees and decided they would be much better in the long run if we selectively thinned,” said Kruger. “We are leaving as many healthy trees we can and selected the best of the bunch randomly so there isn’t a cookie-cutter type forest.”

Kruger said that it allows the needles and branches to rot and replenish the soil faster than just falling the trees and leaving them whole on the ground. “Our project is about conservation and restoration – visitors have to remember this was logging country before we took over the property,” said Kruger. “There are many stands across the park that are in a fit of stress because they were planted so close together 30 years ago. They were being grown for harvest on a 40 year rotation but our goal is to achieve long term heath of the park’s forest for many, many decades to come.”

The project will give the remaining trees more room to grow and that will ensure the long term health of the parkland’s forests.

Back on the Banks-Vernonia Trail, you reach end of the line in the town of Vernonia and be sure to roll up to the town’s remarkable Pioneer Museum. Inside, you will discover that a different sort of logging heritage runs deep in what was once a “company town.” For many decades, Vernonia’s life blood centered on the “Oregon-American Lumber Mill” that ran around the clock and employed nearly two thousand workers in the early 1920s. And back then, “the trees were unlike anything you’ve ever seen,” according to volunteer Tobie Finzel.

The Vernonia Pioneer Museum houses a remarkable photo collection from the heydays of old growth logging and provides visitors with a snap shot on a time in Oregon – it is worth your time to visit.